Dr. Charcot's Hysterical Women

Horace Williams House, Chapel Hill, 2023.

-

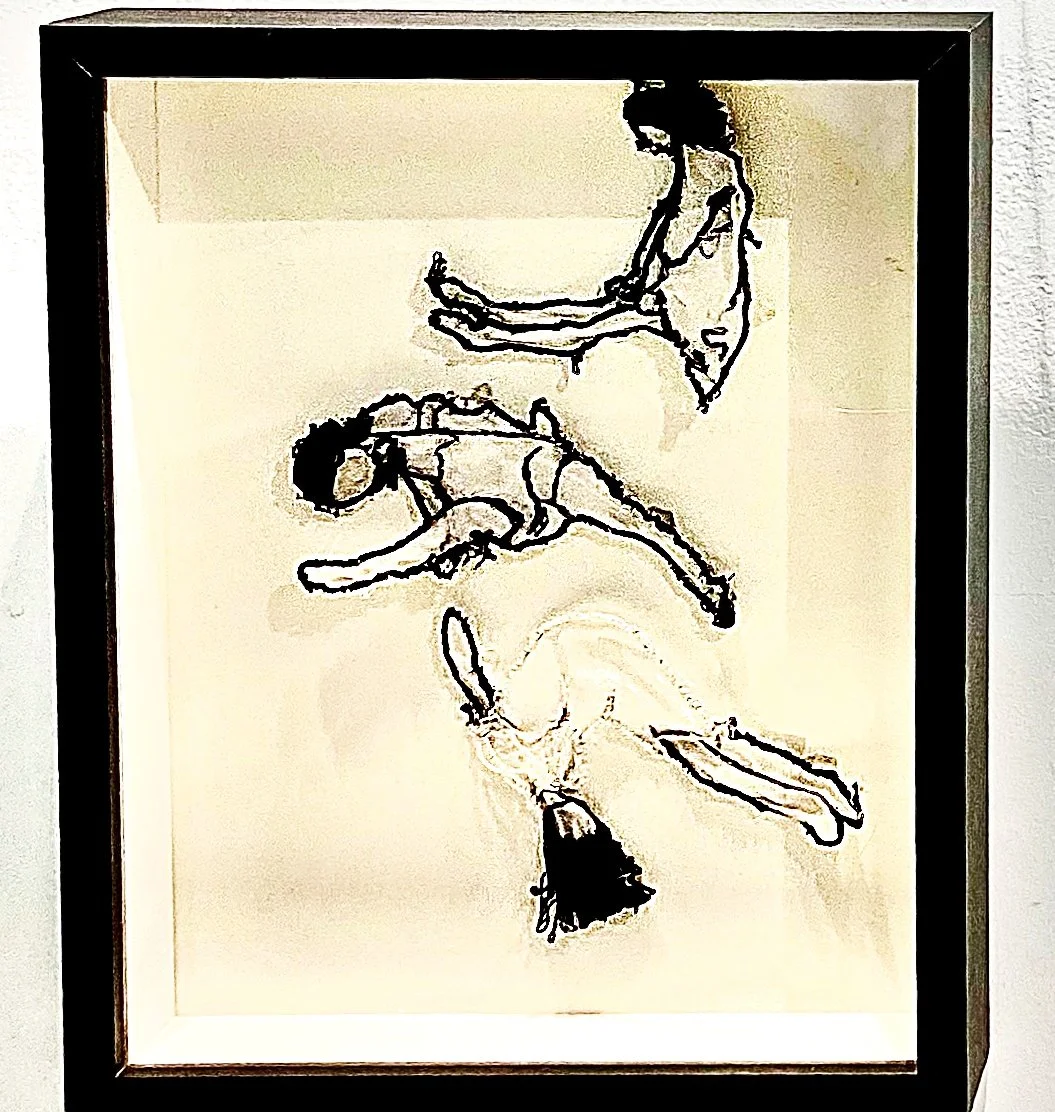

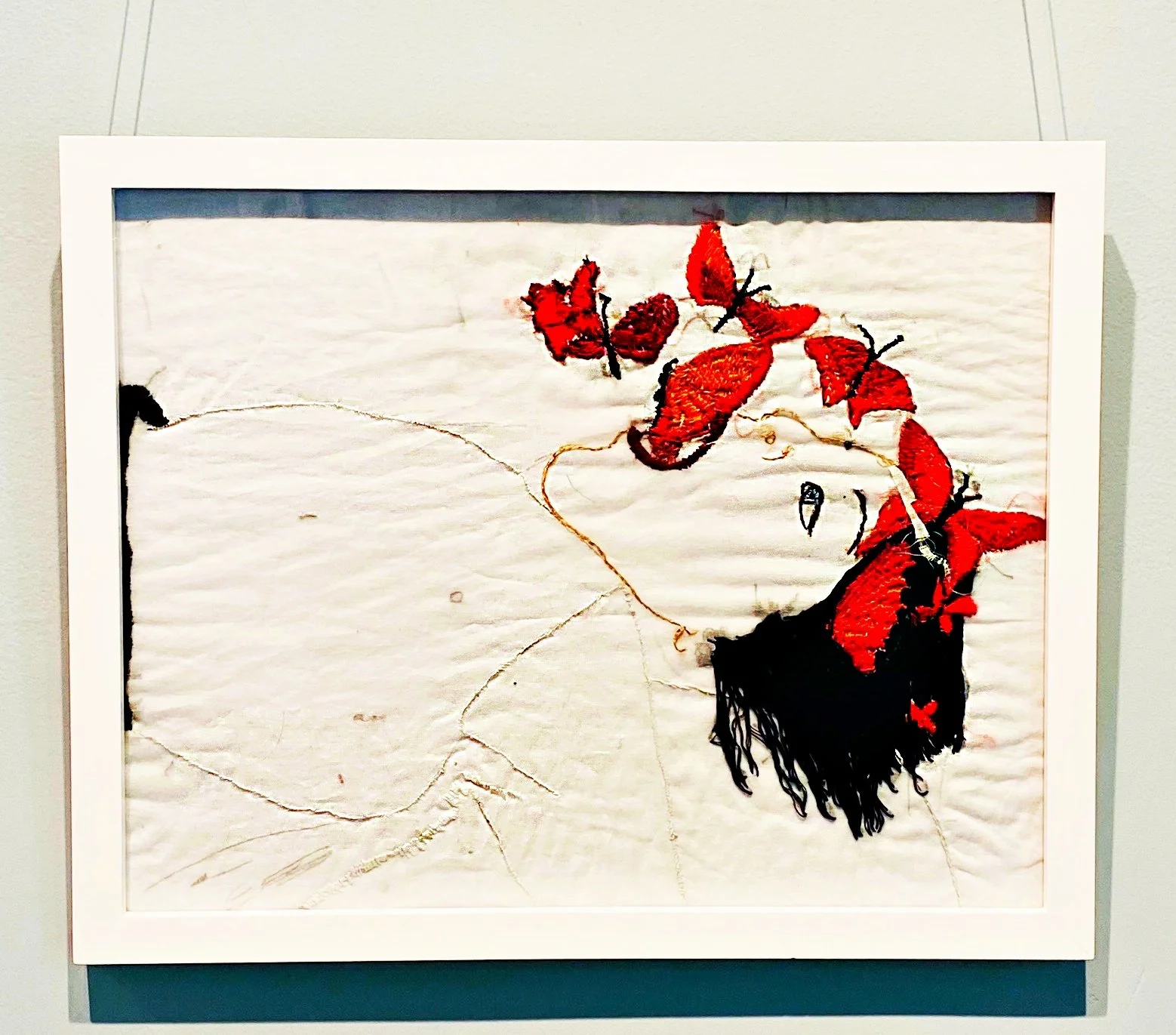

Like butterflies suspended by pins, everything here wants to move, but can’t.

For centuries, the word “hysteria” was used to describe a panoply of illnesses including nervous anxiety, faintness, irritability, uncontrolled movements, intermittent and overt sexual desire or lack thereof and any behaviors that made society uncomfortable

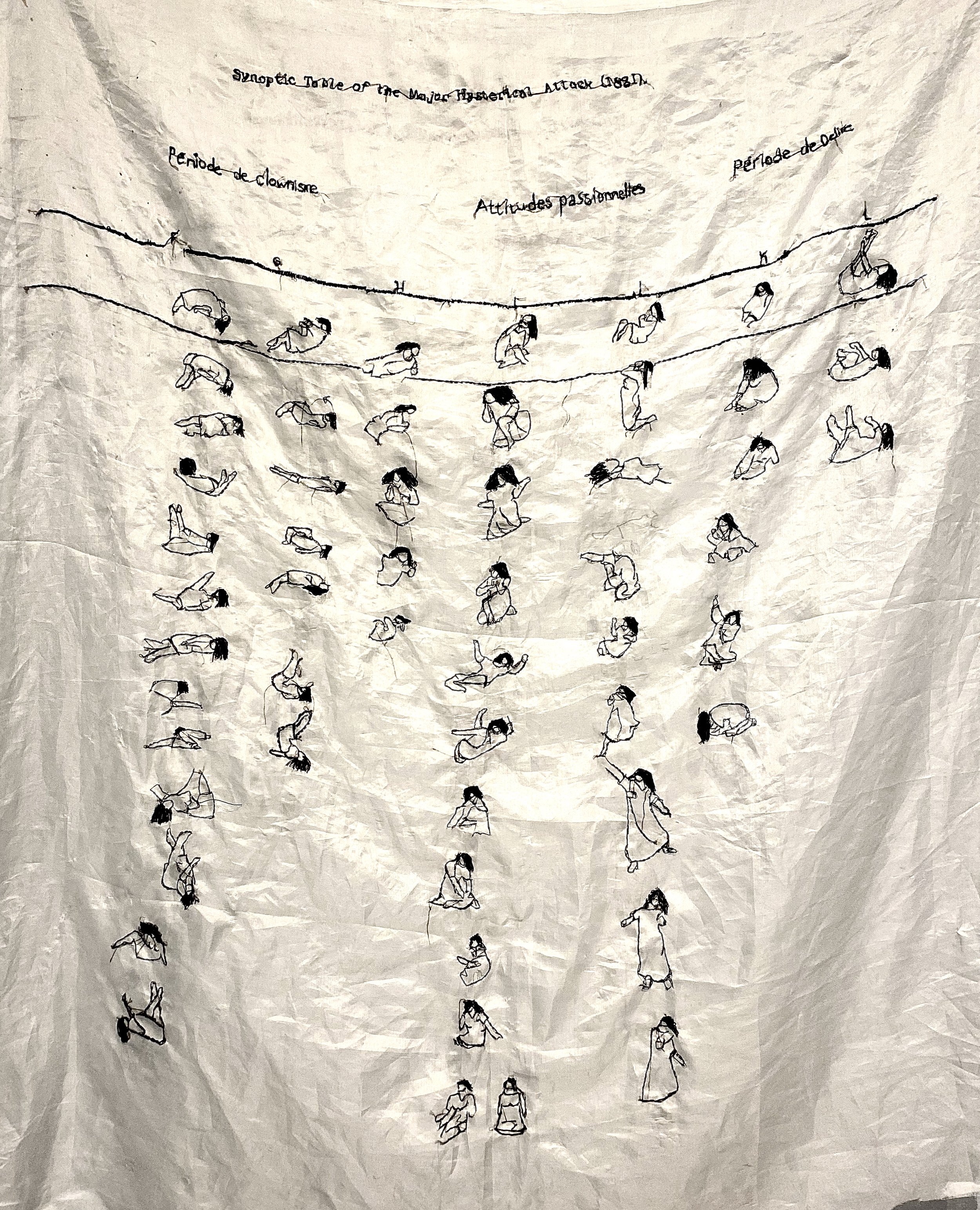

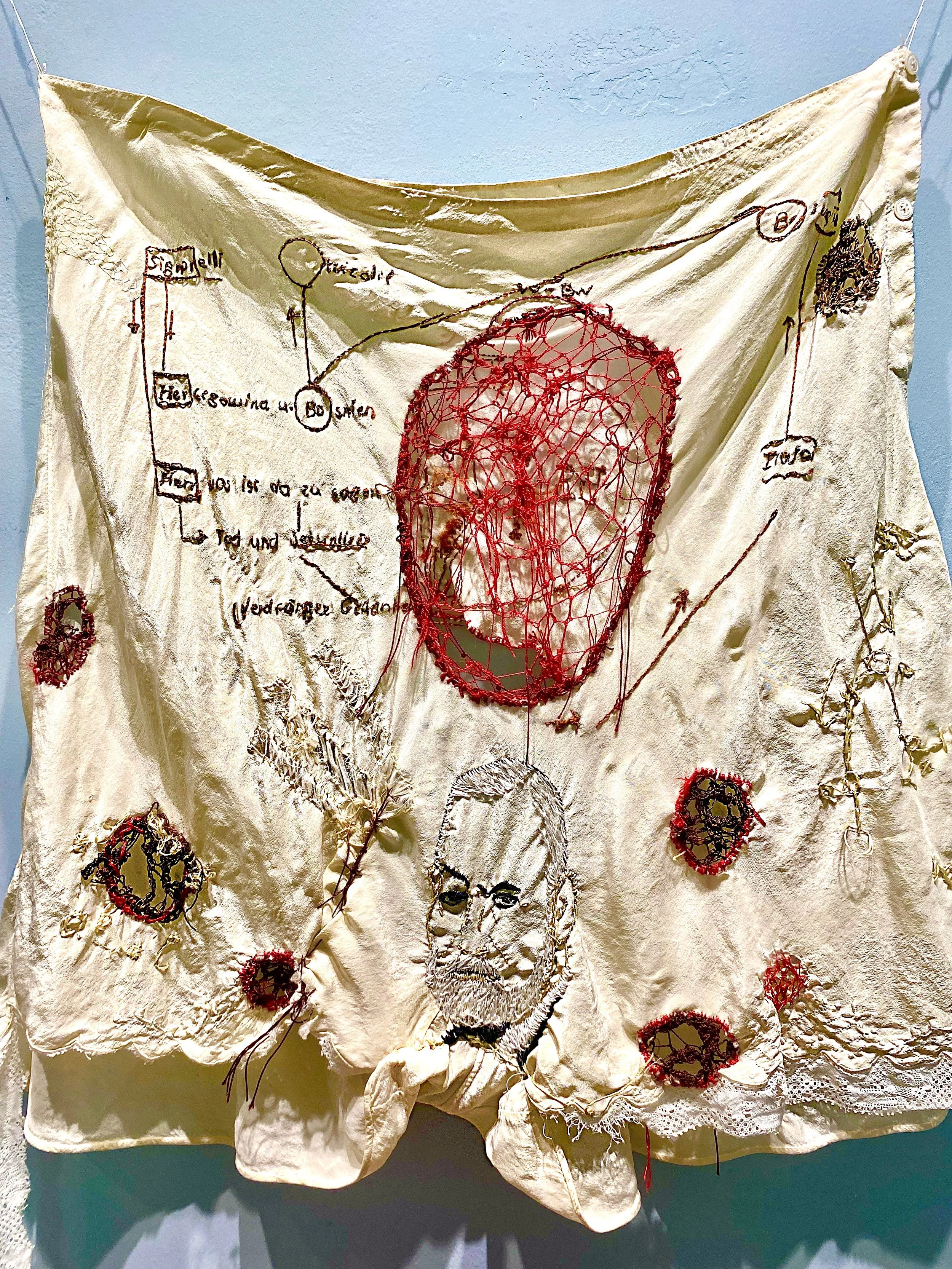

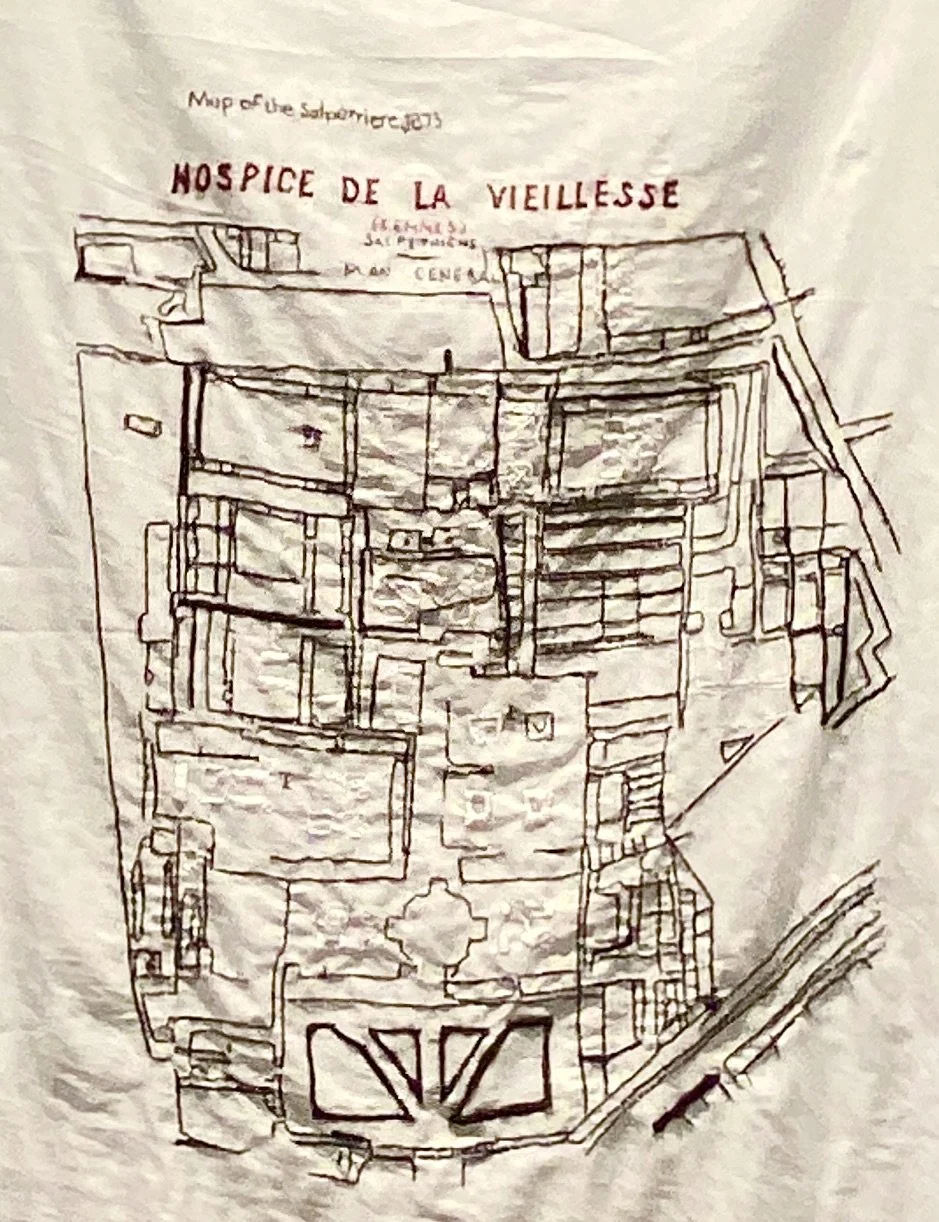

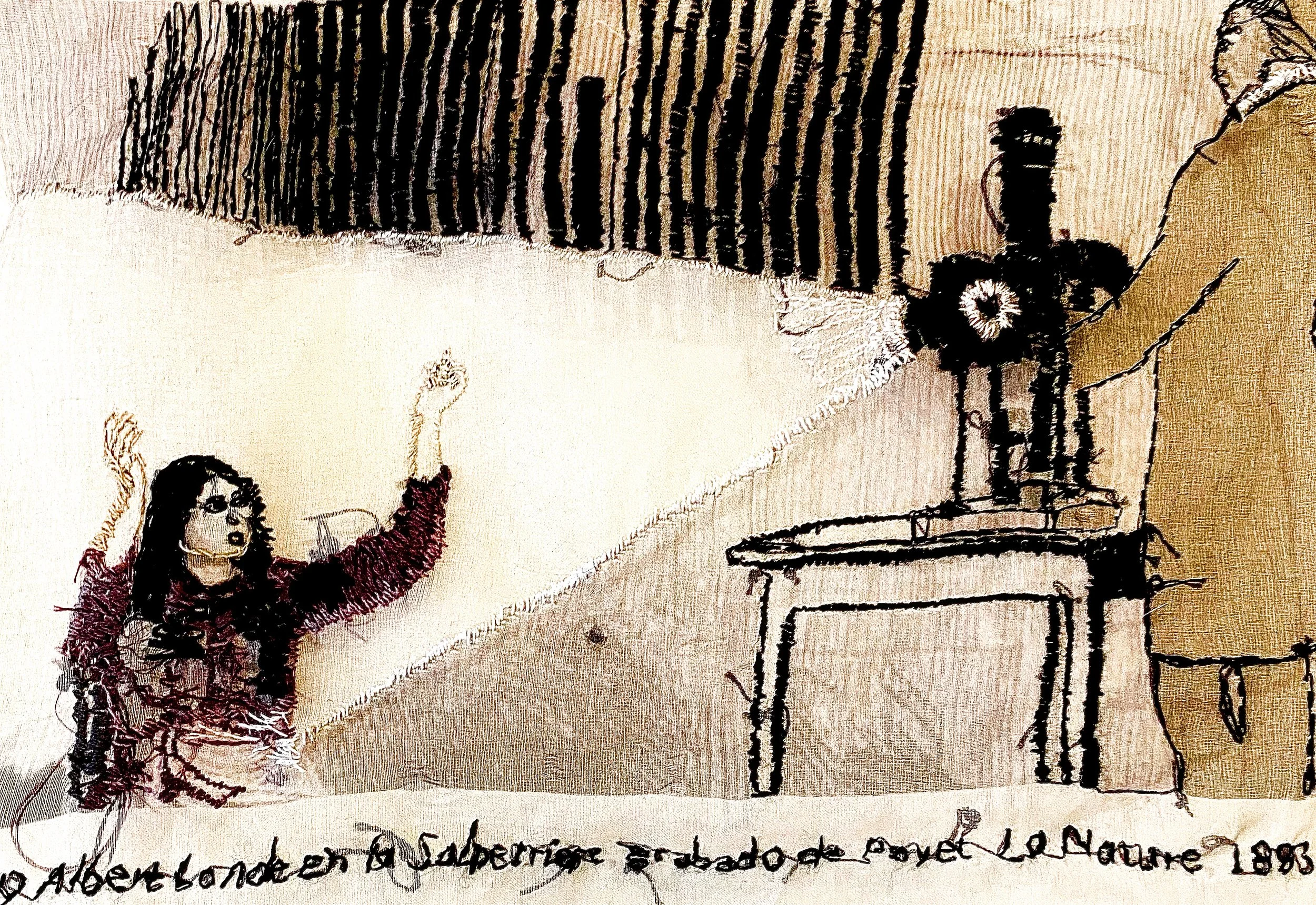

In the late nineteenth century, French neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot began using the recent technology of photography to have images taken of female ‘hysterics’ in his unit at the Salpêtrière hospital. His intentions were positive. Unlike his contemporaries or post-Charcotians, Charcot did not believe that hysteria was a symptom of degeneracy. His Tuesday lectures were soon attended by physicians from all over the world, including an inspired Sigmund Freud. Charcot wanted to completely characterize the physical manifestations of the ‘disorder’. The resulting multi-volume work, Iconographie photographique de la Salpêtrière (1875-1880), with photos taken by Paul Régnard and Albert Londe, suggested a scientific legitimacy to the disorder of hysteria and was intended to be used as a pedagogical aid for other physicians. Charcot was entranced by the fact that the most distinguishing characteristics of these "hysterical" symptoms was that they could be reproduced.

The images captured within Iconographie photographique de la Salpêtrière contain everything: poses, attacks, cries, “attitudes passionnelles,” “crucifixions,” “ecstasy,” and all the postures of delirium. A mutual benefit of enticement was established between physicians, with their insatiable desire for images of Hysteria, and hysterics, who willingly participated and actually raised the stakes through their increasingly theatricalized bodies. Photography was the ideal tool to develop the connection between the fantasy of hysteria and the fantasy of fixing it. In this way, hysteria in the clinic became the spectacle, and the patients became a strange form of living dolls.

With Charcot we discover the capacity of the hysterical body, which is, in fact, extraordinary. It is extraordinary; it overtakes the imagination. But whose imagination?

Using embroidery to revisit or reinterpret images created through the male gaze, as well as navigate the constant push and pull of personal agency, feels transgressive and defiant. The intense emotion and the tattoo-like quality of the stitching make any textile appear once inhabited, like a suicide note or the lingering scent of absence. It also exposes a mysterious complicity between those patients and doctors: a relationship of desires, gazes, and performance.

This project is supported by the United Arts Council of Raleigh and Wake County, Raleigh Arts, and the North Carolina Arts Council, a division of the Department of Natural and Cultural Resources.